Truist Bank Routing Number

The routing number for Truist Bank is 057000668. This routing number is the same for all states so don't worry about using the correct routing numbers for your recipients within the US. Read on to know more about what is a routing number and how to use it for wire transfers.

Truist Bank routing numbers for wire transfers

What is a routing number?

A routing transit number is a nine-digit number that identifies a bank or financial institution when clearing money for electronic transfers or processing checks in the US. The American Bankers Association (ABA) established these numbers. The terms «routing,» «transit» and «ABA» number are all used today and have the same meaning.

Where is a routing number used?

A routing number is used when processing check and electronic transactions, like fund transfers, direct deposits, bill payments, and digital checks.

Fedwire money transactions are processed by the Federal Reserve Banks using routing transit numbers. They are required by the Automated Clearing House (ACH) network to permit electronic transactions, such as wage and pension payments.

How to find a routing number?

There are many ways to find your bank’s routing number.

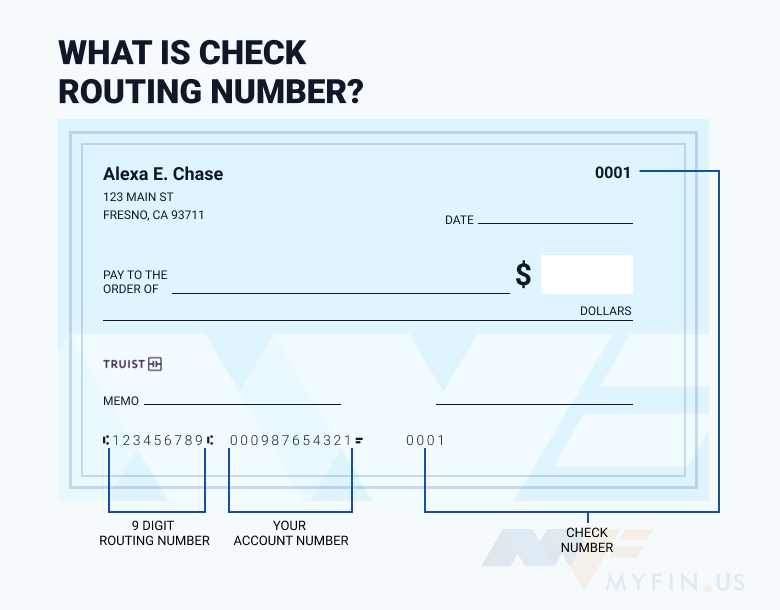

You can usually find it on your check or bank statement. As shown in the picture, the routing number is at the bottom left corner of a check.

SWIFT code VS routing number VS IBAN

It’s normal to get confused by all the acronyms and codes involved in (international) wire transfers. These three, SWIFT code, routing number, and IBAN are the most common ones, and it's important to know what each one means.

We’ve already explained what’s a bank routing number and it’s also worth mentioning that they’re only used in the US. So, if you have a US bank account and want to make a domestic wire transfer, you'll need the routing number of the recipient’s bank.

A SWIFT code (also called BIC) is used for the identification of banks and financial institutions globally when making international money transfers. This code will identify the country, bank, and branch of the recipient's account. If you’re the one making an international transfer to a beneficiary outside the US, you’ll need to enter the SWIFT code of the beneficiary’s bank. If you’re the one receiving an international transfer, you’ll have to provide your bank’s routing number, as well as its SWIFT code.

While a routing number and a SWIFT code are both numbers used to identify a specific financial institution, an IBAN is a personal bank account number. It is generally used for international transfers in Europe and several other territories. It is not used in the US (as well as in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand). So, if you’re sending or receiving an international transfer from Europe (and several other territories), you will need an IBAN.